Have you ever secretly smiled when you saw a competitor struggle, or felt a small thrill when a rival team lost? Why does that feeling happen, and what does it mean for our social and business lives?

In this article, you will learn about schadenfreude—the pleasure we feel when someone else faces misfortune—especially in the context of competition. We will explore its psychological roots, how it appears in business and everyday life, and ways to handle it responsibly. By the end, you will have a clear understanding of why schadenfreude happens, how it affects our behavior, and what you can do about it. Ready to begin? Let’s dive in!

Introduction to Schadenfreude in Competitive Contexts

In this section: We will define schadenfreude, see how it developed from philosophical to psychological understanding, and learn about its common presence in competitive environments. You will also see why it is economically and socially important to study this emotion.

Conceptual Framework of Schadenfreude

Schadenfreude is a German word meaning pleasure taken in someone else’s trouble. Though we now use it in modern psychology, it has roots in older philosophical discussions about human nature and empathy. Today, we see schadenfreude in many competitive settings—like sports, business, and personal rivalries—where winning feels even better if someone else loses.

The Three Driving Forces Behind Schadenfreude

- Aggression-based schadenfreude often appears when there is a strong “us versus them” feeling. We enjoy an outgroup’s failure because we see them as enemies or threats.

- Rivalry-based schadenfreude emerges from direct competition between individuals or teams, where one side’s loss fuels the other side’s satisfaction.

- Justice-based schadenfreude arises when we feel someone “deserves” misfortune, so we see their downfall as fair or right.

In competitive environments, these forces can blend together, creating a powerful emotional reaction.

The Business and Social Value of Understanding Comparative Satisfaction

From an economic point of view, if we know why people feel happy when a competitor fails, we can predict certain market reactions—like how consumers might switch brands. Socially, understanding schadenfreude can improve group dynamics, reduce harmful rivalry, and guide ethical decision-making. In everyday life and business, this knowledge helps us see where negative or competitive emotions might hurt relationships or create conflict. Marketers, sports managers, workplace leaders, and consumer psychologists all benefit from recognizing these emotions.

We’ve discovered why schadenfreude matters and how it relates to competition. But what sparks these feelings inside us at a deeper level? Let’s explore the psychological foundations next!

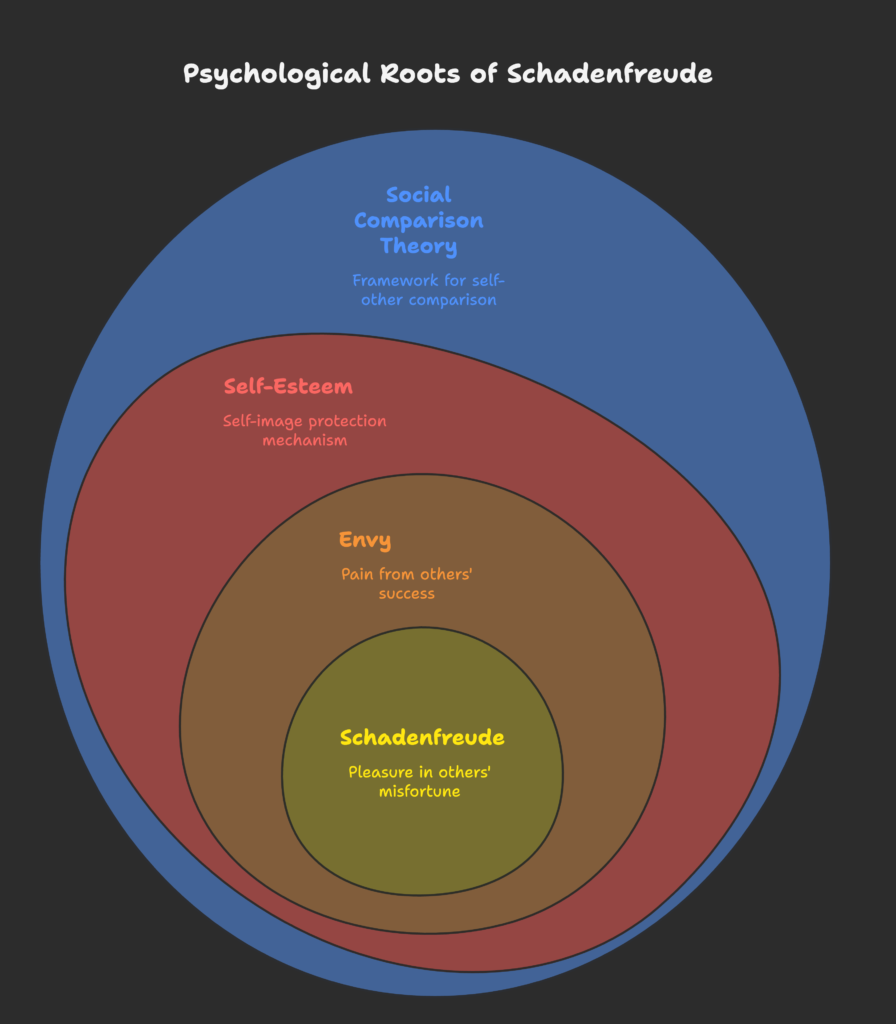

Psychological Foundations of Comparative Emotions

In this section: We will look at how social comparison theory, self-esteem, and envy set the stage for schadenfreude. By the end, you will see how our perceptions of ourselves and our envy toward others can turn into pleasure at their misfortune.

The Social Comparison Theory Framework

Social comparison theory says that we compare ourselves to others—sometimes looking at people “above” us (upward comparison), and sometimes looking at people “below” us (downward comparison). In a competitive setting, if someone else’s failure makes us feel better about our own position, we might experience schadenfreude. In some cultures, these comparisons are very open and direct; in others, they might be more subtle but still powerful.

Self-Esteem and Schadenfreude

Research shows that people with lower self-esteem may feel stronger schadenfreude. Why? Because seeing someone else lose can protect their self-image. If we feel threatened or insecure, watching a rival stumble can give us a short-term emotional boost. However, not everyone reacts the same way—personality, social context, and personal history also play a role in how strongly we experience schadenfreude.

Envy as a Precursor to Schadenfreude

Envy often appears before schadenfreude. When we envy someone, we feel pain because of their success or status. If that successful person then fails, it can relieve our painful envy and create pleasure. Research even shows that certain brain areas light up when we feel envy and then light up again when we see the envied person having a setback.

Now we know the psychological roots of comparative emotions. But what does the brain do when we feel this way? Let’s find out in the next section!

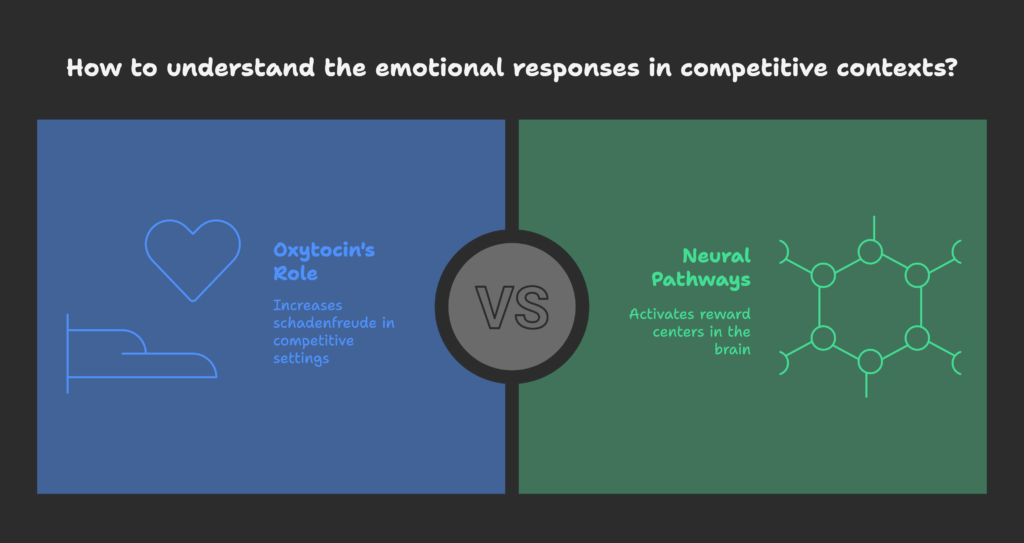

Neurological Mechanisms of Comparative Satisfaction

In this section: We will explore how the brain processes schadenfreude. You will learn about the reward system, the hormone oxytocin, and how the pain or misfortune of others can trigger pleasure responses.

Neural Pathways of Schadenfreude

Scientists have used brain imaging to study schadenfreude. They found that the ventral striatum, a key part of the brain’s reward system, is active when we experience pleasure at another’s misfortune. This suggests that schadenfreude is not just a social concept—it also has a distinct biological pattern in our brains.

The Oxytocin Connection

Oxytocin is often called the “love hormone” because it promotes bonding and trust. Surprisingly, studies show that it can also increase schadenfreude in competitive settings. In a friendly context, oxytocin encourages kindness, but when there is an “us versus them” feeling, it can increase satisfaction at an opponent’s downfall. This reminds us that human emotions are complex and can switch between positive and negative, depending on the context.

The Pain-Pleasure Connection in Social Contexts

Watching someone we dislike face trouble can spark reward centers in our brain. Research also shows gender differences in how people respond to a rival’s misfortune when they believe it is “deserved.” At the same time, the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex is linked to feeling envy, which can flip into pleasure when the other person fails.

We have uncovered the fascinating biological side of schadenfreude. Next, let’s see how different types of competition can shape these feelings!

Types of Competition and Their Influence on Schadenfreude

In this section: We will look at how schadenfreude changes in different competitive environments. We will see examples from zero-sum competitions, social status battles, and consumer markets.

Direct Competition and Zero-Sum Contexts

In a direct, zero-sum game, your gain is someone else’s loss. Sports are a classic example: if one team wins, the other team loses. This setup naturally boosts schadenfreude, because resources or trophies are limited. When rivals fail, it feels extra satisfying.

Status Competition and Prestige Hierarchies

In many workplaces or social circles, people fight for prestige or recognition. If a high-status person slips, observers who felt threatened might secretly celebrate. Negative stereotypes about powerful groups can make their downfall more “enjoyable” to those below them. The idea that someone who once “had it all” is coming down can trigger intense schadenfreude.

Consumer Competition and Marketplace Behavior

Even shoppers can experience schadenfreude. For instance, fans of a certain brand may enjoy seeing a competitor’s product fail. If you bought a phone, you might feel satisfaction when a rival phone brand has a big recall. This satisfaction can lead to stronger loyalty toward your chosen brand.

So far, we’ve seen how different forms of competition can boost schadenfreude. Next, let’s explore how group identity shapes these feelings in social and organizational settings!

Group Identity and Comparative Satisfaction

In this section: We will discover how our sense of belonging to a group can intensify schadenfreude, especially in sports fandom and workplace situations.

Ingroup-Outgroup Dynamics in Schadenfreude

People often feel more schadenfreude toward outgroup members than toward their own group. If we see an outgroup as a threat or hold prejudices against them, we may feel pleasure when they fail. In contrast, if we view them as neutral or friendly, we are less likely to feel such satisfaction. Building cooperation and empathy can reduce these negative emotions.

Sports Fandom and Team-Based Schadenfreude

Sports fans often show deep loyalty to their teams, and rivalries can last for decades. Die-hard supporters love it when their rivals lose, even if it doesn’t directly benefit their own team’s position. Brain scans reveal that fans may literally feel rewarded when a rival team fails, showing how group identity makes schadenfreude stronger.

Organizational and Workplace Comparative Emotions

In a competitive work environment, employees might quietly celebrate a coworker’s failure, especially if they see that person as competition for promotions or praise. This can create a cycle of negative behavior, encouraging gossip and reduced trust. Understanding these emotions can help leaders build a healthier and more cooperative environment.

We’ve looked at how group membership can affect schadenfreude. Next, we’ll see the individual factors—like personality traits and culture—that also shape these feelings!

Individual Factors Influencing Comparative Satisfaction

In this section: We will talk about how personal traits, gender, cultural background, and development over time affect the intensity of schadenfreude.

Personality Traits and Schadenfreude Susceptibility

People who have what psychologists call the Dark Triad traits—narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy—often report stronger schadenfreude. Their lack of empathy or their manipulative nature might make them more likely to take pleasure in others’ downfalls. High aggressiveness can also add to these feelings.

Gender and Cultural Variations

Studies find some differences between men and women regarding the triggers for schadenfreude and how openly it is expressed. Culture also matters. Some societies see open competitiveness as normal, leading to more open displays of schadenfreude, while others discourage strong competitive emotions. Social norms shape whether people admit to feeling this pleasure or hide it.

Developmental Trajectories of Comparative Emotions

Young children can feel a form of schadenfreude quite early, although it might look different from adults. During adolescence, as social comparisons increase, teens might feel envy and rivalry more intensely. With age, many people learn healthier ways to handle these emotions, but the roots of schadenfreude can remain throughout life.

We’ve just seen how personality, culture, and age can influence schadenfreude. But what about factors like deservingness, status perceptions, or closeness? Let’s dive into those moderating elements!

Moderating Factors of Competitive Schadenfreude

In this section: We will discuss how ideas of fairness, status, and social distance shape the way we feel pleasure from others’ setbacks.

Deservingness and Moral Judgment

We often justify our schadenfreude when we think the other person “deserves” their bad luck—like a cheater getting caught or a rude coworker being reprimanded. This moral angle can make us feel that our enjoyment of their misfortune is fair and less shameful.

Status and Competence Perceptions

If someone is seen as powerful, rich, or very competent, their failure can look more dramatic. People might root for a high-status person to fail just to bring them “back down to earth.” On the flip side, if someone loses status before failing, the schadenfreude effect might be smaller.

Relationship Closeness and Social Distance

We are less likely to feel schadenfreude toward close friends or family members, unless there is intense rivalry. The more distant or anonymous a person is, the easier it becomes to laugh at their failure. Online platforms, for example, can encourage schadenfreude because we feel less emotionally connected to strangers.

So far, we’ve covered many triggers and shaping factors. How does this all show up in consumer behavior and the marketplace? Let’s explore that next!

Consumer Behavior and Marketplace Schadenfreude

In this section: We will learn about how brand rivalries, product failures, and ethical marketing practices can stir up or calm down schadenfreude among consumers.

Brand Rivalry and Consumer Schadenfreude

When fans identify strongly with a brand—like a tech company or a car maker—they can enjoy watching a competing brand fail. Product recalls, negative reviews, or public scandals feed this feeling. This emotional reaction can strengthen loyalty to the favored brand and even lead to online cheering when a competitor has a setback.

The Impact on Consumer Choice and Satisfaction

Studies suggest that if your rival brand fails, you may feel happier about your own purchase, even if the product quality has not changed. That extra feeling of triumph can boost repurchase intent and long-term loyalty. Basically, someone else’s misfortune can make your product experience seem even better.

Ethical Marketing Considerations

Some companies may be tempted to use negative ads or direct comparisons to “encourage” schadenfreude. But this strategy can be risky. Many consumers dislike “bullying” tactics and may react negatively if a brand appears too aggressive. Marketers have to find a balance between standing out in a competitive environment and staying ethical. Regulations often limit overly negative or misleading ads to prevent harmful rivalry in the market.

We’ve seen how schadenfreude influences buying decisions and brand loyalty. Next, we’ll talk about the methods researchers use to study these emotions in depth!

Methods for Studying Comparative Satisfaction

In this section: We will look at scientific methods—brain scans, experiments, and field studies—to investigate how and why schadenfreude occurs.

Neuroimaging and Physiological Approaches

- fMRI studies: Researchers measure brain activity in the reward centers during schadenfreude.

- Facial EMG: Sensors pick up micro-expressions (like tiny smiles) when people see a rival fail.

- Eye-tracking: Shows how attention focuses on news of a competitor’s trouble.

- Hormonal tests: Help us learn how chemicals like oxytocin are involved in comparative satisfaction.

Experimental Paradigms and Manipulations

In lab settings, scientists create mock competitions to see if participants feel satisfaction at another’s failure. They might manipulate how “high status” a rival is, or how big the competition stakes are, then measure schadenfreude. Group identity priming is also used to see if people favor their own group while enjoying the outgroup’s losses.

Field Studies and Naturalistic Observations

Real-world data offers strong evidence, too. Researchers observe sports fans in actual stadiums or watch how employees react to each other in offices. Consumer behavior studies track how negative news about one brand affects loyalty toward its competitors. This helps us see schadenfreude in action.

We’ve looked at how schadenfreude is studied. Next, let’s discover practical ways to apply this knowledge and reduce its harmful effects!

Applications and Interventions

In this section: We will explore how to reduce harmful schadenfreude in groups, manage competition at work, and use marketing responsibly. You will see how these insights help create healthier social and business environments.

Reducing Harmful Schadenfreude in Groups

Encouraging cooperation instead of direct competition can cut down on schadenfreude. When people work together toward shared goals, the “us vs. them” barrier lowers. Teaching empathy, bringing groups into contact in friendly ways, and highlighting shared interests can also lessen the desire to celebrate someone else’s hardship.

Workplace Applications

Companies can create bonus structures that reward teamwork, not just individual success. Leaders should address toxic rivalries openly, encourage team-building, and promote an inclusive culture. By doing so, they reduce negative comparisons, which in turn decreases workplace schadenfreude.

Marketing and Consumer Behavior Implications

Marketers need to be aware that focusing too much on a competitor’s downfall can backfire and make the brand look mean-spirited. A positive approach—highlighting a brand’s strengths rather than attacking others—can still attract customers without fueling hostility. Ethical guidelines for comparative advertising encourage fair competition that doesn’t exploit harmful emotions.

We’ve learned how to apply these lessons to real life. Let’s tie everything together and look at what’s next for schadenfreude research!

Conclusion and Future Directions

In this section: We wrap up our main findings, consider new topics for future research, and think about the moral questions surrounding schadenfreude in competitive settings.

Synthesis of Key Findings

- Complex Causes: Schadenfreude has psychological, social, and neurological roots.

- Context Matters: Competitive situations, group identities, and moral judgments shape the intensity of schadenfreude.

- Wide Impact: We see it in business, sports, workplaces, and everyday life.

- Practical Implications: Understanding schadenfreude can help us manage competition more ethically and productively.

Emerging Research Directions

- Social Media Impact: Online platforms might increase or reduce schadenfreude in new ways.

- Cross-Cultural Insights: We need more international studies to see how different cultures handle schadenfreude.

- Neurogenetic Factors: Future research could explore how genes and brain chemistry interact with social contexts.

- Developmental Changes: We can study how schadenfreude evolves from childhood into old age.

Ethical and Philosophical Considerations

Schadenfreude raises questions about the value of competition in society. Is it possible to have healthy, friendly competition without wanting someone else to fail? Education and awareness are key. Teaching empathy and cooperation can help balance our natural competitive drive with compassion for others.

Remember, understanding schadenfreude isn’t just about curiosity; it’s also about building better relationships—both personally and professionally.

Quick Note: If you run a Shopify store and are looking to boost your sales ethically and effectively (without relying on competitor failures!), consider trying the Growth Suite application. It helps you manage and grow your business in a sustainable way, ensuring you can stay competitive while maintaining a positive brand image.

References

- Cikara, M., & Fiske, S. T. (2012). Stereotypes and Schadenfreude: Affective and physiological markers of pleasure at outgroup misfortunes. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(1), 63-71.

Link - Cikara, M., & Fiske, S. T. (2012). Their pain, our pleasure: Stereotype content and schadenfreude. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1299, 52-59.

Link - Grimes, A. (2018). The genesis of team rivalry in the New World: sparks to fan animosity in Major League Soccer. Soccer & Society, 19(5-6), 704-723.

Link - Leach, C. W., & Spears, R. (2008). “A vengefulness of the impotent”: the pain of in-group inferiority and schadenfreude toward successful out-groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(6), 1383-1396.

Link - Moisieiev, D., Dimitriu, R., & Jain, S. P. (2020). So happy for your loss: Consumer schadenfreude increases choice satisfaction. Psychology & Marketing, 37(10), 1420-1435.

Link - NPR. (2018, September 4). Competition Fuels Schadenfreude, Research Shows.

Link - Putra, I. E., & Firdaus, E. (2021). Silent Competition among Students: How Schadenfreude and Social Envy Influence Rating-based Achievement Motivation. Journal of Educational, Cultural and Psychological Studies, 23, 41-70.

Link - Shamay-Tsoory, S. G. (2010). The Neural Basis of Competitive Emotions. University of Haifa.

Link - Smith, R. H., Powell, C. A. J., Combs, D. J. Y., & Schurtz, D. R. (2009). Exploring the when and why of schadenfreude. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(4), 530-546.

- University of Zurich. (2019, April 24). Schadenfreude: Your pain is my gain. Neuroscience News.

Link - Wang, X., Lu, K., Qin, H., Chen, P., & Wang, P. (2024). Your Pain Pleases Others: The Influence of Social Interaction Patterns and Group Identity on Schadenfreude. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(3), 607.

Link - Wikipedia. (2023). Schadenfreude.

Link - Zidani, M., & Harun, S. (2023). The Nature of Schadenfreude in Consumption Contexts. Journal of Business and Economic Studies, 14(2), 243-262.

Link